What does Herman Melville have in common with Brian Wilson you ask? Both were quirky, burly men who, at one time or another, sported a bushy beard, but the similarity goes deeper than that.

Born more than a century apart, both men were in their twenties when their first creations received such overwhelming success that thwarted a fuller appreciation of the works now considered the pinnacle of their creativity.

Melville’s Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, sold one-fourth of his first book, a title many would be hard pressed to name (read on for the answer). Upon its release in May 1966, executives at Capitol Records were so anxious about the sales of Pet Sounds they rushed out a greatest hits compilation to assuage the corporate bean counters. Now, both works are considered masterpieces.

Sadly, when he died at 72 in 1891, Melville had been largely forgotten and did not see his masterpiece revered as one of the greatest books ever written. Fortunately, Wilson, now 77, has enjoyed the accolades heaped on Pet Sounds and his creative renaissance helped him finish SMiLE decades after its initial sessions.

So, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of his birth, here’s a primer on the extraordinary life and literary career of Herman Melville, one of America’s greatest authors.

Melville at 200

A Look at the Life of the Author of Moby-Dick

Shortly after midnight on the morning of September 28, 1891, a seventy-two-year-old man died of heart failure at 104 East 26th Street in New York City. It came as a surprise to many New Yorkers, indeed most Americans, as it was widely believed he was already dead.

The once internationally celebrated author had not published a novel in nearly thirty-five years. His books were out of print and at a then-recent gathering of New York literati no one knew he was living ten blocks away. The New York Times marked his passing with a three-sentence obituary in which his greatest achievement, now a revered masterpiece, was misspelled.

Herman Melville—novelist, short story writer, poet, and author of Moby-Dick; or, The Whale—was laid to rest quietly in Woodlawn Cemetery in the north Bronx beside his sons Malcolm and Stanwix, both of whom died young and tragically. It was not until after the centennial of his birth that Melville’s work began to be appreciated by scholars, critics, and book lovers, and he would be acknowledged as one of America’s greatest writers.

Date of Death: September 28, 1891

Descended from Scotch, Irish, and Dutch ancestry, Herman Melville was born August 1, 1819, at 6 Pearl Street in New York City, the third of eight children of Allan Melvill (the family later added the “e” believing it appeared more refined) and Maria Gansevoort. He was named after his maternal uncle. His maternal grandfather, General Peter Gansevoort, had successfully defended Fort Stanwix, which guarded Albany and the vital Hudson River, against the British in August 1777. His paternal grandfather, Major Thomas Melvill, was known as the Hero of the Tea Party for his role in that historic rebellion December 16, 1773. Until his death at age 81, the major enjoyed regaling visitors with a vial of tea ensnared that night in his high top boots. On June 17, 1825, Marquis de Lafayette visited the major while in Boston to dedicate the cornerstone of the Bunker Hill Monument during his triumphant tour of America commemorating the Revolution’s 50th anniversary. Family gatherings were a time to relive his family’s military participation in the nation’s struggle for independence.

On October 9, 1830, eleven-year-old Herman helped his father clear out the remaining light possessions from their home on Broadway in lower Manhattan. Allan’s import business had failed, and he was fleeing creditors. They hurried to the dock at 82 Cortlandt Street where they spent an anxious night aboard the steamer Swiftsure before leaving the next morning to journey 160 miles north along the Hudson River to join Maria and their seven other children to live near her mother in Albany in a rented house provided by her brother Peter. With his father’s financial collapse, Herman’s comfortable world, tended to by nurses, servants, tutors, cooks, and housemaids, came to an abrupt and jarring end.

Herman and his fifteen-year-old brother Gansevoort enrolled at the Albany Academy. The family idolized Gansevoort and Allan often described Herman relative to Gansevoort. Herman was “more sedate” and “less buoyant.” When Herman was seven, Allan sent him to visit his uncle Peter and cautioned, “He is very backward in speech & somewhat slow in comprehension, but you will find him as far as he understands men and things both solid & profound.” A year later, Allan wrote, “You will be as much surprised as myself to know that Herman proved the best speaker” in his class.

In January 1832, after an arduous open-carriage journey in frigid two-degree weather, Allan became delirious and died, leaving his family with crippling debt. That June, twelve-year-old Herman began work as a clerk in the New York State Bank in Albany earning $37.50 per quarter year. The following month a cholera outbreak in Canada threatened Albany via the Erie Canal, forcing Maria and her children to move to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to live with her late husband’s older brother, Thomas, on the family farm. Two days after arriving at the farm, where he enjoyed the camaraderie of his cousins, his uncle Peter demanded Herman return to Albany to resume working at the bank. He made the eight hour coach ride alone.

Portrait of Allan Melville, father of Herman, by John Rubens Smith (American, London 1775–1849 New York), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

By 1834, Melville was clerking at Gansevoort’s thriving cap and fur store until a fire destroyed the business. In September 1836, he reenrolled in the Albany Academy, joined the Young Men Association, and the Philos Logo Society, a debating club. Although his education had been disrupted by his family’s financial plight, his rigorous studies of Greek, Latin, and the Classics, coupled with his own disciplined self-study of Milton, Spenser, Shakespeare, and the Bible, produced an erudite young man with a keen and inquisitive mind, and a striking command of the English language. Always a prankster, he spiritedly terrorized his four sisters with memorized passages of the witches from Macbeth. In his copy of Edmund Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queen, the phrase “Each godly thing is hardest to begin” is checked. But, like many boys his generation, he was also captivated by the adventures in Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe.

In May 1839, the New York Knickerbocker Magazine ran an article by Jeremiah N. Reynolds entitled “Mocha Dick: or, The White Whale of the Pacific,” about the killing of a legendary albino sperm whale. That same month, Melville’s first published writing (“No. 1 Fragments from a Writing Desk”) appeared in the Democratic Press and Lansingburgh Advertiser. A month later, he signed as a cabin boy aboard the St. Lawrence merchant ship from New York to Liverpool where he witnessed abject poverty and learned a harsh lesson when the captain swindled him from his wages. Upon his return that October, he began teaching at the Greenbush & Schodack Academy, across the Hudson River from Albany. In spring 1840, the academy failed and he went unpaid.

On Christmas 1840, in the wake of Richard Henry Dana, Jr.’s just published Two Years Before the Mast, Melville signed aboard the whaler Acushnet and was bid farewell at New Bedford by Gansevoort. Eighteen months later, the ship landed on the Marquesas Islands, where he and Richard “Toby” Tobias Greene jumped ship, traveled inland, and lived among the Typee, who occasionally cannibalized their vanquished foes. A month later, he boarded the Lucy Ann bound for Tahiti. Seven weeks later he boarded the whaler Charles and Henry for the Sandwich Islands (now the Hawaiian Islands). He landed on Maui and took the schooner Star to Honolulu just weeks before the Acushnet, the whaler he had deserted, docked at Maui. He stayed in Honolulu three months working as a sales clerk and pin setter at a bowling alley. Two weeks after his twenty-fourth birthday, he enlisted for two months in the United States Navy, sailing around Cape Horn aboard the frigate United States, on its way home to the Charlestown Navy Yard in October 1844.

Once discharged from the Navy, Melville visited his aunts in Boston and called on Judge Lemuel Shaw at his stately home on Beacon Hill. Shaw had been engaged to his aunt Nancy Wroe Melvill before she died in 1813, and Herman had not seen him in more than a decade. Judge Shaw knew Richard Henry Dana, Jr. and spoke of Dana’s literary success, encouraging Melville to write his own adventures. Melville was delighted to reacquaint himself with Elizabeth Shaw, the judge’s twenty-two-year-old daughter who he had not seen since she was a young girl. Lizzie, as she was known, had been kept apprised of Herman’s adventures and whereabouts as his sisters received his letters from Honolulu.

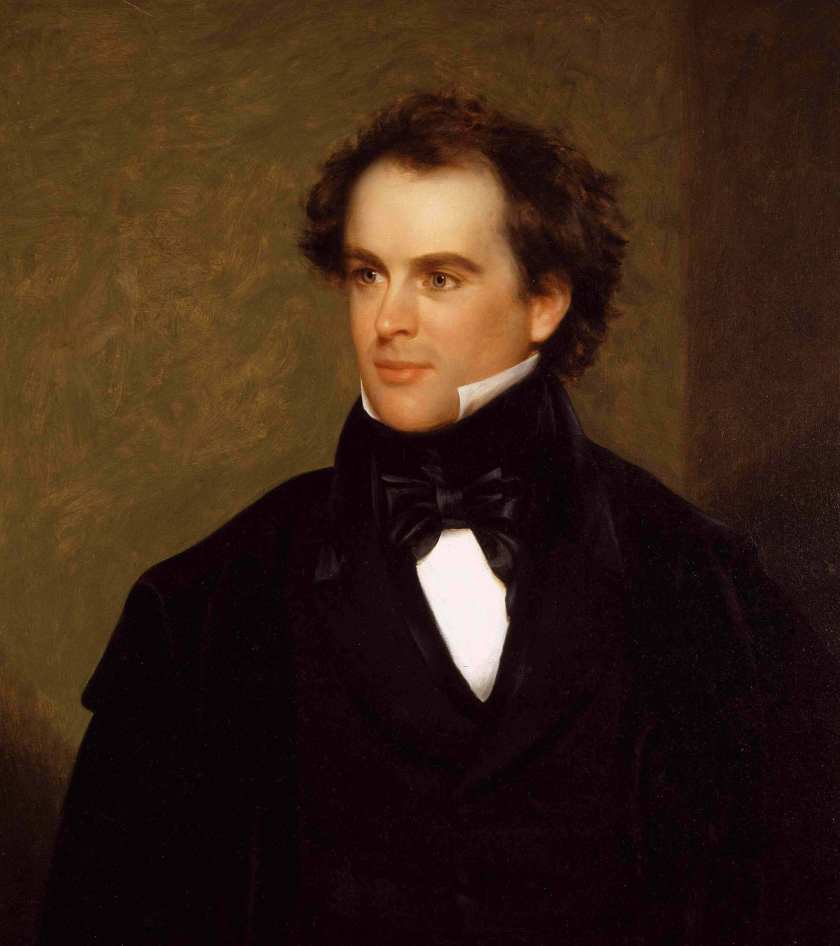

Lizzie was attracted to this restless, mysterious wanderer. Melville had matured into a strikingly handsome and charismatic man. He stood 5’10”, with a mane of thick brown hair combed straight back, a sturdy, prominent nose, and a lush, meticulous beard. His small, piercing blue eyes were said to take you into himself. More than one sea and land companion named a child after him. He was tanned, athletic, and walked with a sensual rolling gait typical of a sailor after years compensating for the pitch of a ship.

He next travelled to upstate New York, surprising his mother and siblings. He arrived October 23, but his homecoming was slightly upstaged by Jesus who the Millerites, a religious sect led by New York farmer William Miller, believed would return to Earth that day. Herman narrowly missed Gansevoort who, as he learned, was now an attorney known as the “orator of the human race” for his tireless campaigning that year for James Knox Polk’s presidential bid against Henry Clay. Gansevoort’s fiery speeches were printed in newspapers throughout the country. Inspired by Gansevoort’s oratorical and political success, and contemplating what to do next with his life, Melville travelled to Manhattan to share in the culmination of his brother’s victorious campaign that election day.

In social gatherings with friends and family, Melville became such a spellbinding storyteller his sisters urged him to write his stories down. And write he did, composing ten novels over the next eleven years.

He was astonishingly prolific considering mid-19th century writing technology. Dipping his steel-tipped metal pen into an inkstand, which in winter rested on a hot brick to prevent the ink from thickening, he wrote in cramped cursive to conserve paper. His sisters spent long days deciphering and copying his manuscript for publishers to typeset. Although he preferred writing by available daylight, describing his eyes as “tender as young sparrows” from a bout of measles when he was seventeen months old, he often would not leave his room until after dark when he would eat for the first time that day. One of the joys in his life was the discovery of Shakespeare’s collected works in large print. Despite these challenges, his London publisher later cautioned he was writing books too rapidly to allow for proper marketing and sales of his current offering.

In early summer 1845, he pitched his first book-length manuscript to Harper and Brothers on Cliff Street at the tip of Manhattan. He sought Harpers because they had published Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast and for their reputation for an effective marketing and distribution network. Harpers rejected it, however, citing “it was impossible that it could be true and therefore was without real value.” Family members later recalled “the Harpers refusing it calling it a second ‘Robinson Crusoe’ embittered his whole life.” In fall 1845, Gansevoort took the manuscript to London where, with a recommendation from Washington Irving, he secured a British publisher (John Murray) and an American publisher (Wiley & Putnam). Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life was published in spring 1846, dedicated with affection and gratitude to Lemuel Shaw who, at the urging of Daniel Webster, had accepted the position of supreme court justice of Massachusetts. Melville proposed to Lizzie and they married August 4, 1847. Judge Shaw’s advances on Lizzie’s inheritance would soon sustain Melville through lean financial times.

Typee was reviewed favorably by Walt Whitman and praised anonymously by Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose observation of “a well-dressed man” was a cheeky reference to cannibalism. Evert A. Duyckinck, the influential editor of Literary World, became Melville’s friend and trusted literary adviser. That May, after complaining of debilitating headaches and vison loss, Gansevoort died in London at age 31. Herman was devastated by the loss of his beloved older brother and literary champion.

In spring 1847, Melville followed Typee with Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas. This time Harpers sprang at the chance to publish the wildly successful twenty-seven-year-old author. Fletcher Harper was just entering his carriage for a European trip when his copy reader hurried to the curb advising Melville was offering them his new book. “Take it at once.” Harpers published Omoo sight unseen.

Typee and Omoo, appearing in such quick succession, made him a literary sensation, scandalously admired and sanctimoniously scorned for his brooding sensuality and inferred sexual liaisons with the beautiful Fayaway among the Typee in the Marquesas. He successfully defended the authenticity of his stories while fielding controversy for his view on the unChristian behavior of some missionaries, his empathy and admiration for the native peoples he encountered, racial discrimination in America, and the barbaric practice of flogging abetted by tyrannical naval sea captains.

Melville began his third book, Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849), with more romantic seafaring adventures, but radically shifted course with dense flights of philosophical musings, and obscure social and political allegory. The public wasn’t buying it. Literally. On a trip to London, where Mardi was published in three volumes, Richard Bentley, his new British publisher, showed him unsold stacks, advising that readers loved volume one and finished volume two, but no one read volume three. Melville defended the disappointing reception writing, “Time would ‘solve’ Mardi.”

His popularity and reputation bruised, Melville responded with an extraordinary surge of creativity, completing two novels in four months, Redburn: His First Voyage (1849) and White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War (1850), reestablishing himself as a readable and reliable author, and profitable client. But Melville detested these works, dismissing them as something he tossed off for tobacco money. But reviewers still unfavorably compared these new books to Typee, which he resented as he did not choose to be “indebted to some rich and peculiar experience in life” for the sole source of his creativity.

While readers on both shores of the Atlantic enjoyed his seafaring tales, Melville was driven to become a great writer. At age 30, he began work on his next novel, which he called his whale book. Melville drew inspiration from the albino whale Mocha Dick and the shocking tale of the whaler Essex, attacked in the South Pacific in 1820 by an enraged sperm whale which sank the ship after ramming it head on. From the crew of twenty-one, only eight survived. When rescued three months later, it was apparent they had resorted to cannibalism to survive.

In summer 1850, while vacationing in the Berkshires in western Massachusetts and in the midst of writing Moby-Dick, Melville met Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose The Scarlet Letter had been published that April and was living in nearby Lenox. That August, Melville interrupted his work on Moby-Dick to write “Hawthorne and His Mosses,” an anonymously-published essay about an earlier collection of Hawthorne’s short stories (Mosses from an Old Manse) so laudatory it helped propel the older writer into long-overdue national recognition (“Hawthorne has dropped germinous seeds into my soul.”).

Melville was so enchanted with the reclusive, darkly charismatic Hawthorne, that in September he moved his wife, one-year-old son Malcolm, his mother, and four sisters from Manhattan to Pittsfield, just north of Lenox, and bought a home he christened Arrowhead for the Native American artifacts discovered while tilling the soil. Melville and Hawthorne enjoyed an affable, affectionate friendship in which they discussed books, writers, life, death, fame, fate, and eternity.

In a lengthy letter to Hawthorne in May 1851, during the final push to complete Moby-Dick, he vented his frustration with the eternal struggle of artists, “What I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot. So the final product is a hash, and all my books are botches.” He bemoaned his literary reputation as “horrible” and worried about being remembered only as “a man who lived among the cannibals!”

Two months earlier, Hawthorne had followed the success of The Scarlet Letter with the Gothic romance The House of the Seven Gables. With his next book, Melville hoped to establish that the United States could serve as the setting of great literature and secure his place in the vanguard of a burgeoning original American literature.

Hawthorne’s friendship had a profound influence on Melville and Moby-Dick. Fifteen years his junior, Melville’s fascination with Hawthorne’s exploration of man’s darker nature informed Captain Ahab’s vengeful, maniacal obsession to rid the world of evil incarnate embodied in the malevolent white whale. With a breathtaking view of a snow-covered Mount Greylock from his study and the warm friendship of Hawthorne’s kindred spirit as an inspirational touchstone, Melville transformed his modest whale story into a psychological masterpiece exploring the darker depths of man’s nature.

On November 14, 1851, on the eve of Hawthorne moving 100 miles east to Concord, he and Melville dined alone at the Little Red Inn in Pittsfield as scandalized townspeople gawked and gossiped. What in the world were these two—one, a recluse known for arousing Puritan sin, the other for his brazen sexuality—talking about in such intimate tones? During dinner, perhaps over brandy and a pipe of tobacco, Melville presented Hawthorne with one of the first copies of Moby-Dick. He watched eagerly as his dear friend read the dedication—“In token of my admiration of his genius, this book is inscribed to Nathaniel Hawthorne.”

In fall 1851, Melville’s magnum opus was published in London in three volumes as The Whale (the title change did not reach London in time) and in the United States in one volume as Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. The early British reviews were mixed and criticized him for something for which he had no control. The one-page epilogue, in which Melville explained his narrator Ishmael was the lone survivor of the catastrophe, was inadvertently omitted from the British edition. Hence, some reviewers unjustly criticized him for not adhering to literary convention that, in order for a narrator to convey a story to readers, the narrator must survive the story. Other critical remarks included “incoherent English,” “forced,” “stilted,” “violations of good taste and delicacy,” and “vulgar immoralities.” Some declared the book blasphemous. Writing in the Literary World, Duyckinck called it “reckless at times of taste and propriety.”

The reviews in the Athenaeum and the Spectator were the two British reviews most often reprinted in the United States, and they were contemptuous of the novel and the novelist. There were many favorable British reviews in late 1851, but Melville may not have seen them as the praise appeared in newspapers that seldom crossed the Atlantic. In contract, in 1847, as secretary to the American Legation in London, Ganesvoort was able forward Herman virtually every review of Typee.

Some American critics lazily reprinted large passages of negative British reviews making it painfully evident they had not read the entire book. Others simply did not understand it. Moby-Dick is indeed a challenging read, incorporating many different literary styles with several excursions from the main action. For all the novel’s colorful musings on the history, anatomy, and physiology of whales (when it was believed they were fish, not mammals), one cannot imagine a modern day editor not wielding a judicious scalpel (think Chapter 32, “Cetology,” in which Melville attempts a systematic description of all the world’s whales).

Moby-Dick remains a faithful portrait of the nineteenth century whaling industry in which sperm whales were mercilessly hunted for their blubber and the waxy liquid called spermaceti found in an organ above their skull, which whalers harvested to meet the demands of many commercial applications including candles, lubricants, and lamp oil. Although Melville extolled the whalers’ courage and the “honorableness and antiquity” of the brutal work, he illuminated a poignant tragedy in which victory was only achieved when the magnificent animal breached to take a breath. Acknowledging the sole motivation of the slaughter, he wrote the whale “must die the death and be murdered, in order to light the gay bridals and other merry-makings of men, and also to illuminate the solemn churches that preach unconditional inoffensiveness by all to all.”

Melville knew he had written a great book. He borrowed money to pay for the printing plates to be produced, hoping to sell the manuscript himself to the highest bidder. When that failed, he contracted with his usual London and New York publishers. He anticipated Moby-Dick would rival, if not surpass, the masterworks of English literature. He hoped sales would ease his mounting financial stress, but Moby-Dick did not deliver him from debt. During his lifetime, 3,715 copies were sold—less than one-fourth of Typee.

In addition to his responsibilities to his wife and two young sons, Arrowhead placed unforgiving demands on his time with planting, harvesting, renovations, repairs, and caring for livestock. He was in debt to his British and American publishers. He borrowed $2,000 from an acquaintance, keeping it secret from Lizzie, to forestall defaulting on Arrowhead’s mortgage held by the original owner. He protested the absence of an international copyright law which left him and other American authors vulnerable to piracy, denying them crucial royalties. He described his financial woes as “Dollars damn me!” His father-in-law remained a staunch supporter and, thankfully, his loans were not expected to be repaid, but it was apparent Melville was borrowing on his children’s inheritance. Lizzie’s stepmother and stepbrother were not so kind, continually sniping at her husband’s sagging reputation. His mother rebuked him for embarrassing her by failing to attend church services regularly. He declined multiple requests from Evert Duyckinck to have a daguerreotype made to promote his image and work. His procrastination led to an unsuccessful bid for the steady paycheck of a political appointment to a foreign consulship, unlike Hawthorne who parlayed his college friendship with Franklin Pierce, whose presidential campaign biography he penned in 1852, into a consulship in Liverpool the following year.

Reviews for Moby-Dick were still appearing as Melville was near completing his next book. On November 17, 1851, he wrote Hawthorne, “Lord, when shall we be done growing? As long as we have anything more to do, we have done nothing. So, now, let us add Moby Dick to our blessings[s?], and step from that. Leviathan is not the biggest fish;—I have heard of Krakens.” He envisioned his next book would surpass Moby-Dick and perhaps rival Macbeth or Hamlet.

Four months after Moby-Dick was published, Melville completed his manuscript for Pierre; or, The Ambiguities, a tragic drama with autobiographical tinges of a noble American family living in pastoral upstate New York. It explored the complexities of the human psyche, man’s darker psychosexual nature, the challenge of achieving self-knowledge, and the eventual delusion of a young idealist struggling with Christian ideals against the harsh realities of the world. It also hinted at an incestuous attraction between the hero and a mysterious woman who presents herself as his half-sister.

Around New Year’s Day 1852, Melville travelled eight hours by train to Manhattan to present it to The Harpers. But the publishers were strict Methodists and did not want to be associated with Pierre. Their solution was to offer Melville a humiliating reduction in royalty from fifty to twenty cents on the dollar after expenses.

Melville would have to sell two and one-half times the number of books to earn what he would have under their previous contracts. Melville brought his manuscript to Duyckinck who proclaimed it immoral and advised against publishing it.

Melville submitted it to Bentley, his London publisher, who proposed half of the net profits, no advance, and editing control to ensure suitability for English readers. Melville declined, countering with a request for a flat £100, pitching the book as “possessing unquestionable novelty” and “very much more calculated for popularity than anything you have yet published of mine.” How, in 1852, Melville thought a book in which the hero is drawn to an incestuous relationship as “calculated for popularity” still mystifies Melville scholars. A Bentley edition never appeared. In late 1852, a few dozen copies appeared in England, published by Harper’s London agent Sampson Low. Melville’s refusal to let Bentley bowdlerize Pierre denied him much-needed revenue and critical revisiting of his previous book (Moby-Dick), a practice which British reviewers were wont to do.

Incensed, Melville reworked Pierre, clumsily inserting an additional 150 pages toward the end to provide his hero a contrived literary past, a platform from which Melville exercised his sardonic wit to rail against self-righteous critics who condemned Moby-Dick, the sad state of American literature, an indiscriminate reading public, Duyckinck’s perceived betrayal, and greedy publishing houses (Pierre’s publisher is Steel, Flint & Asbestos). He cancelled his subscription to Duyckinck’s Literary World.

Whatever short-lived satisfaction Melville received by venting his rage and resentment came with an awful price. His career was essentially over. He had sabotaged his own book, losing authorial control of the plot and introducing significant character inconsistencies. In 1995, the so-called Kraken edition of Pierre excised the ill-advised additions, attempting to present the work before Melville unleashed his frustration.

Rather than offer it to another publisher, Melville accepted Harper’s offer and Pierre was published in July 1852. The critical reception was devastating to Melville’s career. Critics called it “monstrous,” “repulsive,” “an outrage to morality,” “no ordinary depravity,” and “unhealthy.” Duyckinck called it “sacrilegious to family relations.” Melville’s in-laws would have seen the August 5, 1852, Boston Daily Times review denounce Pierre as “one of the absurdist and most ridiculous things that ever ink and paper were wasted on.” The September 7, 1852, New York Day Book headlined its scathing review “Herman Melville Crazy,” hoping “one of the earliest precautions will be to keep him stringently secluded from pen and ink.” Writing in the American Whig Review in November 1852, George Washington Peck took Harpers to task for publishing “such abominations” and urged readers to avoid Melville’s books “as some loathsome and infectious distemper.” Ironically, no reviewer picked up on how Melville had marred a coherent work with his enraged intrusions.

Undeterred, Melville kept writing. On December 2, 1852, he visited Hawthorne in Concord, offering him the idea for a novel of a true story of a woman abandoned by her unfaithful lover-sailor which Melville first heard during a visit to Nantucket with his father-in-law in summer 1852. When Hawthorne declined, Melville wrote the story himself. He completed The Isle of the Cross in spring 1853, but after Harpers declined to publish it, the manuscript was subsequently lost. In November 1853, Melville began work on Tortoise Hunting Adventure, mining his adventures on the Galápagos Islands in fall 1841. Despite a $300 advance from Harpers, he failed to complete it.

He began writing short stories which required less time and provided a much-needed paycheck. Between November 1853 and May 1856, he wrote thirteen short stories published in Putnam’s Monthly Magazine or Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Putnam collected its five serialized stories, Melville added a new story, “The Piazza,” and the six were published as The Piazza Tales in May 1856. It included three of his most enduring stories—“Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street,” still widely anthologized in short story collections, “Benito Cereno,” and “The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles.” The stories were popular with critics and readers, helping to repair his reputation, but sales did not appreciably reduce his debt.

Melville’s work had always drawn the ire of some prominent religious leaders and journalists. Harpers now distanced themselves from the perceived damage Moby-Dick and Pierre had done to their relationship with prominent Methodists and as a Christian bookseller. Melville’s relationship with Harpers further soured when, in December 1853, a fire destroyed the publisher’s warehouse, consuming 494 copies of Pierre and 297 copies of Moby-Dick, leaving only 60 remaining. By his own account, the loss denied Melville royalties upwards of $300 annually. Harpers charged him $1,000 for new printing plates despite having already charged those publication costs. This was especially antagonistic since, in April 1849, at the Harper’s urging, Melville had purchased the Typee plates from Wiley & Putnam and gifted them to Harpers, from which they had profited handsomely.

His next novel, Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile, inspired by the true story of an exiled Revolutionary War soldier who had fought at Bunker Hill, was serialized in Putnam’s Monthly Magazine and published by G.P. Putnam & Co. in March 1855. His final novel, The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade, was published in New York by Dix, Edwards & Co. in April 1857. The publisher dissolved later that year without paying Melville royalties.

Melville’s output declined dramatically over the next three decades as he lectured and turned his hand to poetry. In 1860, Harpers declined a book of his poems which were subsequently lost. In 1863, he sold Arrowhead and moved his family back to Manhattan. In 1866, after six years of unemployment, his termination as a clerk at the New York Custom House was averted by the intervention of Chester A. Arthur, an influential customs official and future twenty-first President of the United States, who admired Typee, Omoo, and Moby-Dick. That year he published Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War, a collection of seventy-two poems about the Civil War. The following year, tragedy struck when his eighteen-year-old son, Malcolm, died from an apparent self-inflicted pistol shot. In 1876, he published his epic poem Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land, inspired by his journey there in winter 1856. At 18,000 lines it is longest poem in American literature.

In December 1885, he retired from the Custom House. The following year, his second oldest child, Stanwix, died at thirty-four from tuberculosis. On March 9, 1887, in a heartrending image of an artist obliterating his art, he requested Harpers melt the printing plates for Mardi and Pierre. When he died at 72 in 1891, he was survived by Lizzie, who died at 84 in 1906, and their two daughters, Elizabeth and Frances.

Within a year of his death, Harpers reprinted Moby-Dick and it is now celebrated as one of the greatest achievements in American literature. Melville’s critical reputation has steadily flourished and he is now admired as a literary genius woefully underappreciated during his lifetime. Moby-Dick has been the subject of numerous editions, translations, adaptations, critical analysis, television mini-series, feature films, and other dramatic renditions. In his 2017 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Bob Dylan remarked about Moby-Dick, “That theme, and all that it implies, would work its way into more than a few of my songs.”

1984, Literary Arts Series

The manuscript of his novella Billy Budd, A Sailor (An Inside Narrative), which Melville was still revising when he died, was discovered by Richard Weaver, his first biographer, in a trunk of his belongings and published posthumously in 1924 at the beginning of the Melville revival.

As we mark the bicentennial of his birth, the question arises whether Melville will be read a century from now? In fact, with increasing demands on our time and the near constant distraction of social media, is anyone reading Melville now? Perhaps not as widely as he should be. Students of great literature will always revel in discovering him. Lovers of great books will find solace in his poetic, evocative language, joy in his warm, amiable voice, wonderment in his complex thoughts and marvelous disorderliness, his incisive illumination of universal subjects that still mystify us. For readers willing to invest the requisite time to appreciate his intricate genius, reading Melville is embarking on an enchanting, sometimes turbulent, always rewarding, journey—a voyage still worth booking 200 years after his birth.

Excellent post. I’m already won over to Melville (and have always been a Beach Boys fan). I still have a few to read but Moby Dick, Billy Budd and Bartleby are all books I admire hugely. I’ve even started a few blog posts myself looking at Billy Budd from a legal perspective. I look forward to reading more of yours.

LikeLike