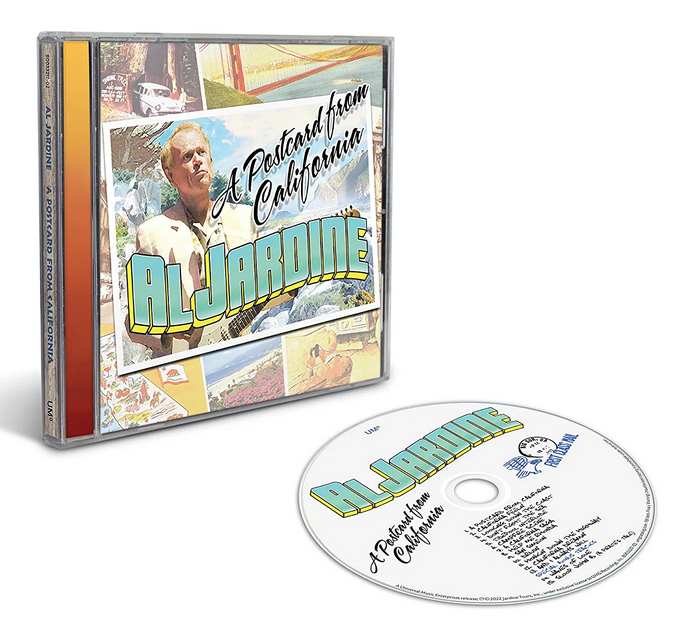

Available Digitally for Streaming and Download; Rereleased on Compact Disc

A Postcard from California, Al Jardine’s delightful debut solo album, was released digitally for streaming and download worldwide by Universal Music Group (UMG) September 2, 2022, and rereleased on compact disc December 9. This wider distribution will help bring this joyous, life-affirming music to new generations of music lovers.

I spoke with Al recently about this re-launch of A Postcard from California. But first, a little background on the history of the album.

Postcard was recorded in Al’s Red Barn Studio. It was first released as a digital download in 2010 and contained a dozen tracks. A subsequent CD release in 2012 added three additional songs. A promotional Extended Play CD previewed four songs before the CD was released that spring. In Japan, Postcard was issued with two additional bonus tracks—an alternate version of “Waves of Love” and “Eternal Ballad,” a poem by Vietnamese spiritual teacher Ching Hai which Al set to music. Vinyl enthusiasts were treated to a thirteen-track release of Postcard on translucent blue vinyl for Black Friday Record Store Day in 2018.

The expanded Postcard’s 15 songs are a mix of new Jardine compositions, fresh takes on songs from his released Beach Boys catalog, and newly completed gems from the vault. The tracks are loosely sequenced as a carefree jaunt along scenic California State Route 1, hugging the stunningly beautiful Pacific coastline. In addition to his famous bandmates, Al recruited an impressive list of guest vocalists, his sons, Adam and Matt, and several talented lyrical and musical collaborators.

I mentioned to Al that, much like Pet Sounds and Sunflower, I thought A Postcard from California is best enjoyed listening in its entirety—start to finish. “It really is compositional,” Al reflected. “One song does lead to another and allows you to take a deep breath, relax, and enjoy the ride.”

The title track kicking off this musical travelogue was inspired by the Jardine family trek from upstate New York on their way to sunny Californ-i-a in 1952. After the second world war, many Americans flocked west in search of a new beginning in a land of hopes and dreams which Salinas native John Steinbeck helped immortalize. Although he could not have been aware of it at the time, Al’s life would be transformed by his father’s decision to leave his teaching post at the Rochester Institute of Technology in upstate New York and accept a position with the Royal Blueprint Company in San Francisco. Donald Jardine was almost 40, Virginia Loxley Jardine, Al’s mother, was 37, his brother Neal was 13, and Al would turn 10 that September 3.

I asked Al what it was like to put himself in his dad’s shoes while he was writing the title track. “It was kind of natural. I just imagined what it would be like. It’s a recollection of sorts. I read some notes about his journey and I kind of relied on that and my memory of his quest to go out and to find an opportunity out west. It was a very folky kind of thing in the tradition of the American move after the war. Everybody was going west having an uplifting feeling that there was a new opportunity. I romanticized it a little bit.”

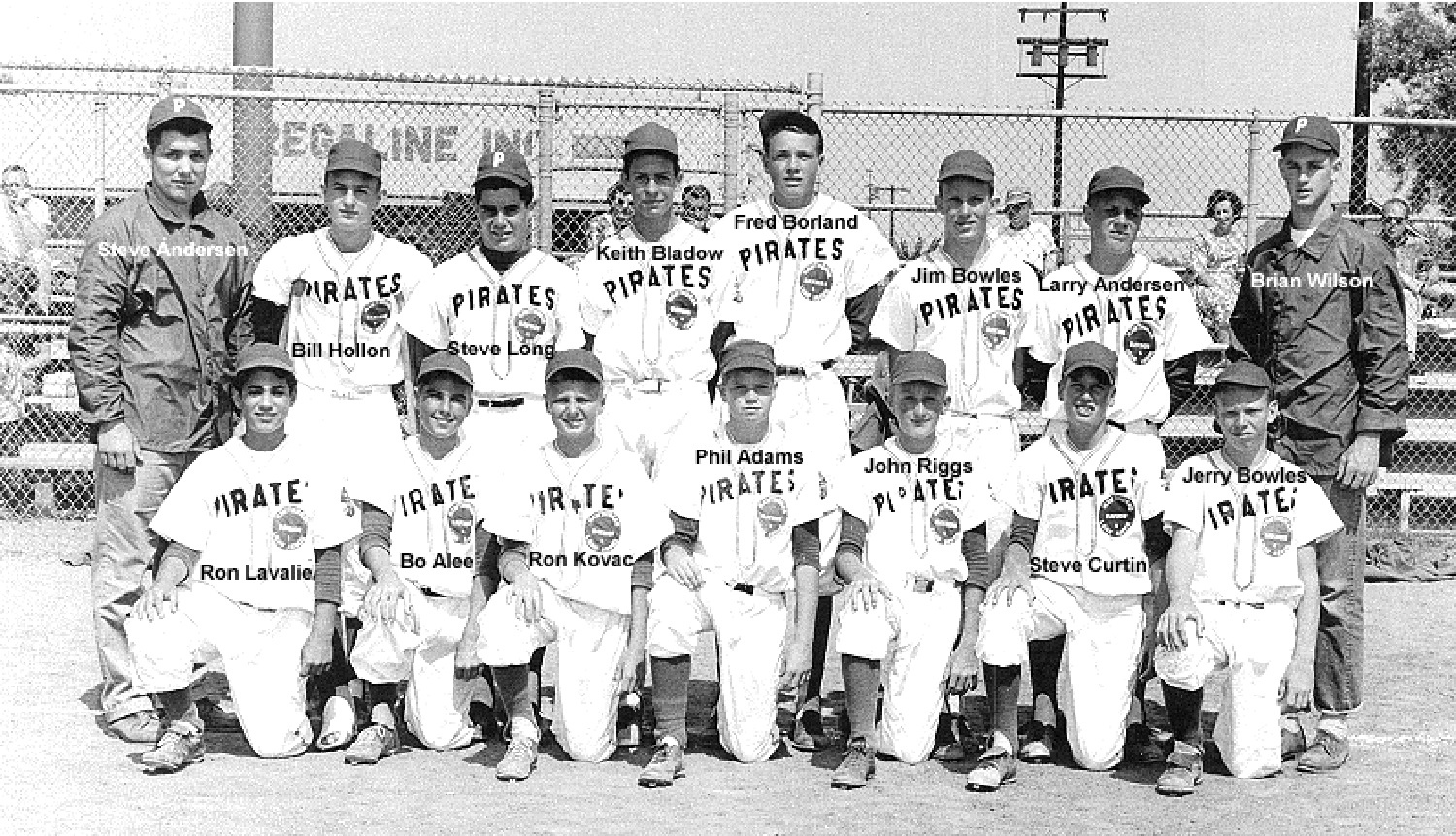

Although I imagined the cross-country trip may have produced some uncertainty and anxiety in the young family, Al assured me that was not the case. “It wasn’t such a risk for us as a family,” Al recalled. “My dad used his Underwood typewriter, which I incorporated into the lyrics, to get employment before making the big move. He already had it all set up. He knew what he was doing. And my mother knew what she was doing. She wanted to get out of that cold northeastern snow by Lake Ontario. That is what drove us west. There was no anxiety about it. It was a thrill. We got to explore a new place.” Don flew out first to rent an apartment in a neighborhood south of San Francisco and put down some roots. A few months later, Virginia and the boys flew out to join him. The furniture made a separate journey. It was Al’s first plane ride and he remembered a long, circuitous flight routed through Dallas. Of course, as Beach Boys fans well know, the family did not remain in the Bay Area. In 1955, Royal charged Don with replicating his success with their blueprinting plant in the LA area. The family was ready for the move as Al recalled they had discovered San Francisco was “was colder than hell.” They moved to Torrance, a suburb of Los Angeles, and, in September 1956, Al enrolled at Hawthorne High School where he would eventually befriend Brian Wilson.

Al sets the tone of the journey in the first verse of A Postcard from California with that rich, warm, familiar voice Beach Boys fans have long enjoyed and still admire (“Now you know that I’m going out west / I think that it’s for the best / Hopes and dreams are what this nation’s built on / They wrote me a letter back / Said get yourself out here fast / We’ll send for your things and put you in a nice hotel”). After the chorus, with its infectious sing-along melody, Glen Campbell picks up the story in the third verse (“I tried you on the telephone / I didn’t find you at home / The lines were down, I guess this note will have to do / Now leaving like this ain’t right, but I had to take the morning flight / I love you girl and I’m already missing you”). Al recalled, “I asked Glen about it one day, when he was singing the lead, ‘What does this remind you of?’ I called you in on this because I felt your vibe. It just comes through the song. He said, ‘Oh, that’s Lineman.’ What he meant is that it feels like ‘Lineman.’ Glen gave it that authentic “Wichita Lineman” vibe. He just nailed it. It also sounds like ‘Rhinestone Cowboy’ in terms of the melodic structure.”

In “California Feelin’” Al extols his adopted home state’s warm clime, natural beauty, and plentiful citrus, set to a beautiful piano, whistling, and mournful harmonica. Written in 1974 by Brian Wilson and poet Stephen J. Kalinich, the song was previewed for rock journalist Timothy White during the launch of the Brian’s Back campaign in 1976 but remained unreleased. Brian recorded it with his new band in 2002 for Beach Boys Classics Selected by Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys version, along with Brian’s original demo, were included on the Made in California box set in 2013. On Postcard, Al slows the tempo and sweetens his stripped-down production with Matt Jardine’s unmistakable falsetto. Interestingly, in place of the fourth verse which Brian included (“You’re a river runnin’ through me / You hold me through the storm”), Al sings (“Look at the orange groves / Taste the grapefruit from a grapefruit tree / Feel the loveliness and beauty of that California feeling”).

The soothing sounds of gently breaking waves and billowing percussion trails into “Looking Down the Coast,” a Jardine original once part of a planned trilogy along with a tune called “Song of the Whales.” In a storytelling tempo, Al sings of California’s rugged coast and vibrant ecosystem of whales, otters, condors, eagles, and grizzlies. The alternating verses are sung in a slower, somber tone, exploring the wonderment of discovery of early European settlers accented with Spanish-style acoustic guitar. William Faulkner, born in Annapolis, Maryland, and raised in Carmel, California, contributes a beautiful Jalisco harp, the quintessential Mexican folk harp.

Probyn Gregory, a multi-instrumentalist in Brian’s touring band, plays a subdued French horn.

Breaking waves and the mournful song of a whale begins “Don’t Fight the Sea,” an environmental plea to treat the Earth’s oceans and the life within them with respect. It features the lead vocals of Al and the late Carl Wilson, and backing vocals from Brian Wilson, Mike Love, and Bruce Johnston. A music video features Al, Brian, Mike, and Bruce in the studio interspersed with images of ocean life and humanity’s often mindless and cruel practices toward marine life. The song has an interesting genesis. It was written by Canadian singer songwriter Terry Jacks as “Y’ Don’t Fight the Sea,” scoring him a #31 hit in Canada in 1976. The Beach Boys worked on the song April 27 and 28, 1976, for possible inclusion on 15 Big Ones. However, it was not included when that album was released that July 5.

In the press release accompanying Postcard’s rerelease, Al commented, “‘Don’t Fight the Sea’ started a long time ago with a Canadian friend of mine, Terry Jacks, who was kind enough to allow me to rewrite his song for a solo album that Mike Love and I were planning around an ecology theme. I asked Matt Jardine to help me with the lyrics. I always envisioned it to be the quintessential environmental song, a big statement, but I could never get all the guys together to finish it. I started with Carl, Bruce (Johnston) and myself on backgrounds, then years later Brian put on his falsetto, and just recently Mike recorded his baritone signature line. To top it all off, I added Matt and friend Scott Mathews to the track, to give additional vocal support to the core group; all this over a period of thirty-plus years. I guess persistence pays off!”

- Al Jardine, Don’t Fight the Sea

It was not the first time the Beach Boys passed on a Terry Jacks-associated song. On July 31 and August 4, 1970, Jacks produced a Beach Boys recording of “Seasons in the Sun” written by Belgian singer songwriter Jacques Brel in 1961 and reworked with English lyrics by American singer-poet Rod McKuen in 1963. The Kingston Trio were first to record an English version of the song which they released on Time to Think in December 1963. When the Beach Boys decided not to release “Seasons in the Sun,” Jacks recorded his own version. The melancholy theme of love and loss struck a chord with the American public and it topped the charts for three weeks in spring 1974. Whether the Beach Boys could have equaled that chart success is an interesting, albeit unanswerable, question. In 2011, Al released “Don’t Fight the Sea” on seven-inch black vinyl and seven-inch opaque white vinyl with the proceeds benefiting tsunami relief in Japan.

“Tidepool Interlude,” a poem by long-time Beach Boys collaborator Stephen J. Kalinich set to piano, guitar, and percussion, is a musical spoken segue narrated by Alec Baldwin who recorded his recitation in a New York studio. A plaintive ship’s bell, lapping ocean waves, and sea birds cawing, introduces this love letter to California exploring the picturesque coastal towns of Monterey, Big Sur, Carmel, and San Onofre. Baldwin was enthusiastic about the project and even suggested some lyrical changes. “I was really impressed with his delivery,” Al noted. “He asked, ‘Wouldn’t it sound better if you said this?’ Well, sure, give it a try, it does seem to sound better. He was contributing a lot of his own energy.”

With its nostalgic harmonica, banjo, and clanging railroad spikes, “Campfire Scene” is an evocative prelude to “A California Saga,” Al’s highlight from the Beach Boys 1973’s Holland where it was titled “California” as the third song in the “California Saga” trilogy. Al’s voice blends beautifully with the distinctive harmonies of David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Neil Young. I commented that had Graham Nash loaned his vocal support, Postcard would have featured an informal CSN&Y reunion. But Nash declined to participate. Al explained, “Graham was very defensive. He thought I was trying to steal their sound. Literally. He was quite upset. When in fact I was just trying to get some harmonies down with good singers. I didn’t have any more Beach Boys voices, so I had to rely on those other great singers. My sons Matt and Adam really helped out. I joked with Graham later at the Grammys, ‘Hey, I didn’t need you on this after all. I got Glen Campbell.’”

Steve Miller shares lead vocals with Al on a folksy homespun “Help Me Rhonda,” a #1 single for the Beach Boys in spring 1965 which famously featured Al’s lead vocal. “Everybody was so helpful,” Al recalled appreciatively. “Steve Miller diverted his private jet to come in and do his lead on ‘Help Me Rhonda’.” Michael “Flea” Balzary of the Red Hot Chili Peppers plays bass on this exuberant version reminiscent of the joyful abandonment of the sessions for Beach Boys Party!

“San Simeon,” a new song by Al and Scott Slaughter, and Al’s favorite on the album, is set around this central coastal town halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The song highlights the area’s natural beauty including a walk along scenic Moonstone Beach, a stretch of rocky beach known as Piedras Blancas (Spanish for “White Rocks”), home to a northern elephant seal rookery, and La Cuesta Encantada (Spanish for “The Enchanted Hill”) the scenic bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean on which publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst built a lavish estate to house his art collection. Known colloquially as Hearst Castle, this National Historic Landmark draws more than 800,000 visitors yearly. After spending a week at Hearst Castle on the Enchanted Hill, Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw reportedly remarked, “The way God would have done it if he had the money.” Al, Matt, Adam, and Dewey Bunnell and Gerry Beckley of America, provide lush background harmonies.

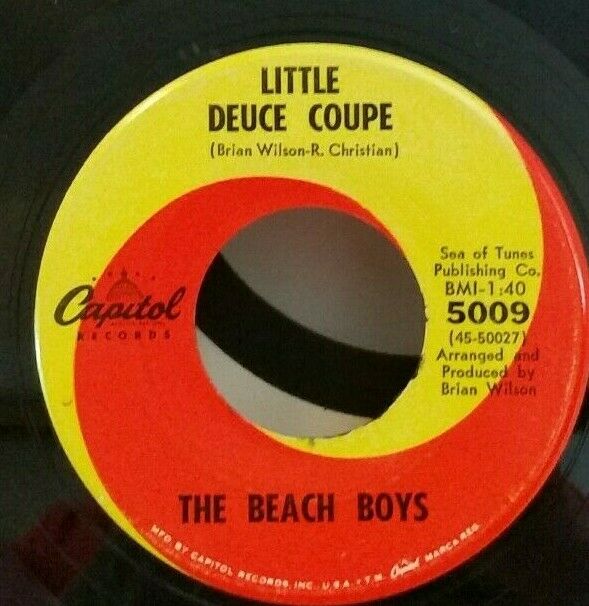

The next two songs, “Drivin’” and “Honkin’ Down the Highway,” pair up nicely to explore California’s fabled automobile culture which the Beach Boys helped immortalize. “Drivin’” is a happy song about the simple joy of cruising California’s legendary coastal highways. Al shares lead vocals with Brian Wilson, Dewey Bunnell, and Gerry Beckley. The song features a wink to “409” with a whimsical reference to “saving my pennies and my dimes,” a nod to the band America’s “A Horse with No Name” and “Daisy Jane,” and a prescient reference to recent prices at the pump. Michael Lent and David Marks, who replaced Al in the Beach Boys from mid-February 1962 to October 1962, contribute tasty guitar licks over a propulsive rhythm track.

“Honkin’ Down the Highway,” a driving Brian Wilson composition that kicked off the Beach Boys Love You in 1977 with a stand-out Jardine lead vocal, receives a spirited production with guitars, piano, minimoog, drums, cowbell, an appropriately honking sax solo by Ritchie Cannata, and a police siren as Al playfully intones “Hey buddy, you better slow down there. I clocked you at 140 with the top down.” The musical journey builds to an unexpected a cappella ending with, as the liners make a point of noting, “really big Queen style vocals.”

“California Dreamin’” receives a pensive interpretation with a sparse instrumental track of acoustic guitar, B3 organ, Cajon drum box, and folky atmospheric percussion provided by sometime touring Beach Boy John Stamos on bongos. Al sings the lead-off chorus, Glen Campbell sings the verse (“I stopped into a church / I passed along the way”), and David Crosby provides soothing vocals echoing Al’s vocals. Written by John and Michelle Philips, the song was a #4 hit in 1966 for the Mamas and the Papas and has long been identified thematically with the Beach Boys. They scored a #8 hit on the Adult Contemporary chart in 1986.

“And I Always Will” is a lovely ballad and Al’s testament to his love for Mary Ann Jardine, his wife of thirty-eight years. “She didn’t think it was about her,” Al shared. “I had been writing it for quite a while. She was certain it was about my first wife. But I assured her that it was indeed about her, and she encouraged me to finish it.” I mentioned the song could become a wedding standard. “Someone did call me and ask about playing it for their wedding,” Al confirmed. “And we became good friends. They write me all the time. They were thrilled to have the song.” Al shared his musical inspiration for the song. “I did rip off Chopin to some degree. His beautiful Étude Op. 10.” When I mentioned Johann Sebastian Bach’s influence on “Lady Lynda,” a Jardine and Ron Altbach composition from the Beach Boys L.A. Light Album in 1979, which was indeed about his first wife, Al good naturedly joked, “Yes, I’m good at lifting beautiful melodies.”

“Waves of Love,” a vintage Jardine composition which current collaborator Larry Dvoskin helped finish, features Al sharing lead vocals with the late Carl Wilson in one of Carl’s last recorded vocals. “Waves of Love 2.0,” featuring a new East Coast mix by Larry Dvoskin, was released as a CD single in 2021. The 2022 rerelease features a newly remastered and extended version of the song which features veteran Beach Boys touring musicians Ed Carter, Michael Meros, and Mike Kowalski.

“Sloop John B.” closes out the album and is given a playful retelling as a children’s song detailing the sloop’s encounter with a pirate ship. With new lyrics and revamped story line, the beloved seafaring tale transforms into a grandfather and grandson adventure tale. A CD of the song first accompanied A Pirate’s Tale, an illustrated children’s book Al published in 2005. Al and Matt sing all the vocals, and Al plays 12 string guitar, bass, and harmonica, and his son, Drew, plays five-string banjo.

I asked Al about dedicating Postcard to “all the animals we love and who love us back!” “We had just lost our beautiful little English bulldog Mimi,” he reflected. “I was quite affected by it.” Pet Sounds, indeed.

“I can’t believe it’s been twelve years since Postcard came out and I thank everyone involved in the production and creation of this album to help me get my songs out there,” says Al. “Brian’s advice to aspiring young songwriters has always been ‘finish your songs’ so I took it to heart and I hope everyone who has listened to A Postcard from California feels my excitement and enthusiasm for this great land and sea of ours and our need to protect it forever. Thank you for all your support over the years, it is greatly appreciated.”

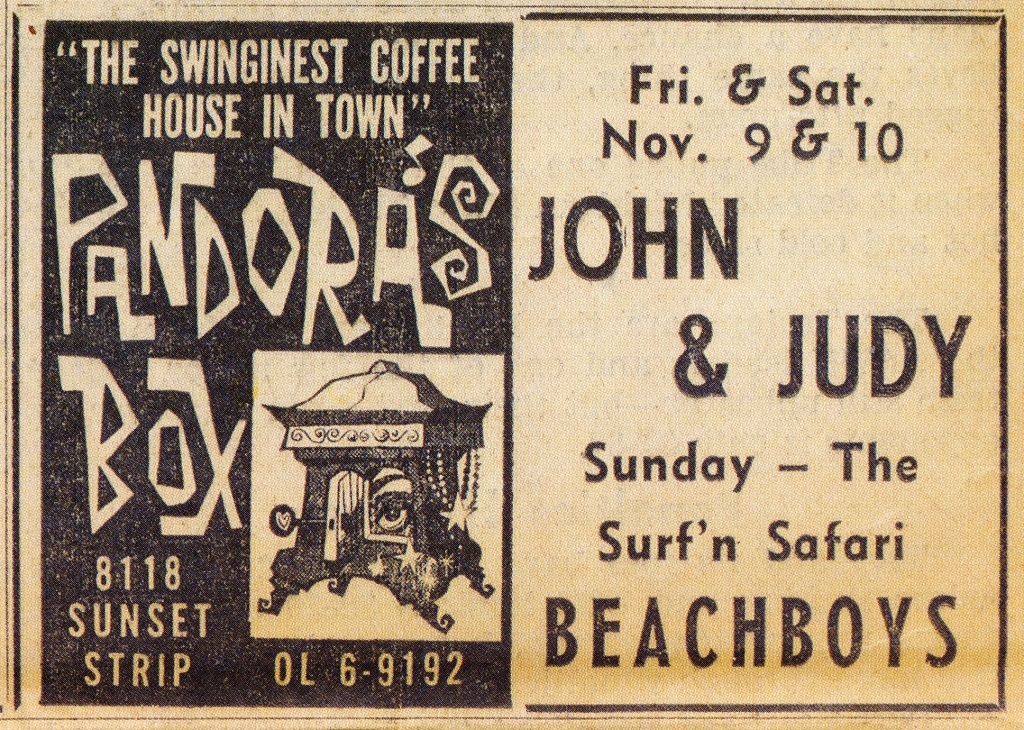

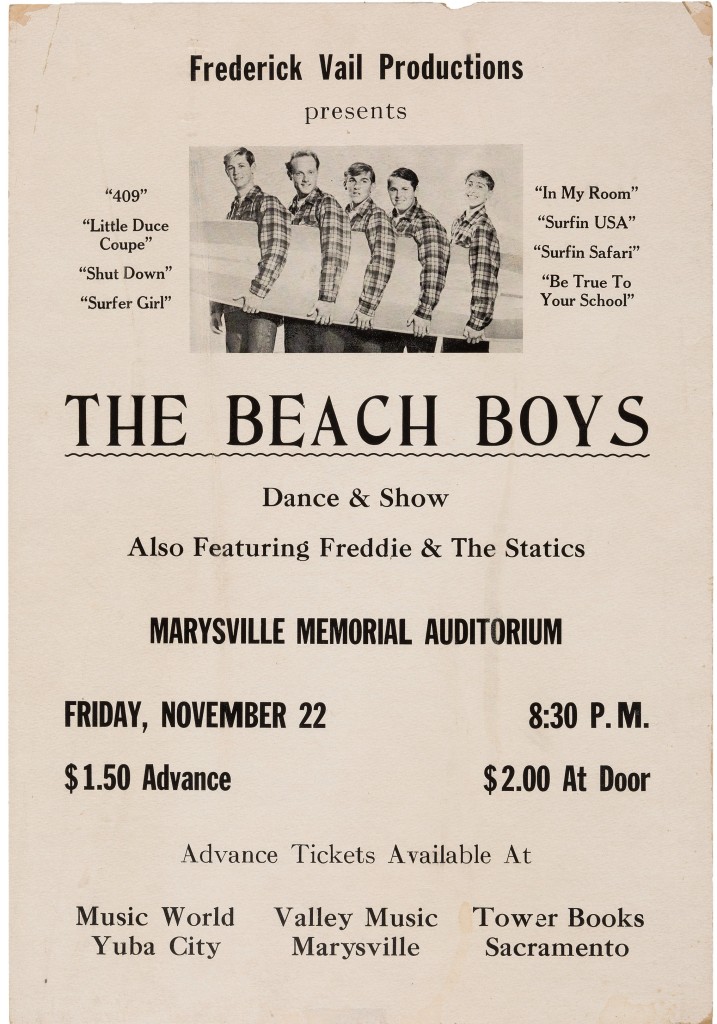

Davis became aware of the Mixtures through Dick Moreland, a former disc jockey on Oxnard’s KACY-AM and later program director on KRLA. Davis and Moreland conceived of the KRLA/Friday Night Dance and enlisted KRLA disc jockey Bob Eubanks as master of ceremonies.

Davis became aware of the Mixtures through Dick Moreland, a former disc jockey on Oxnard’s KACY-AM and later program director on KRLA. Davis and Moreland conceived of the KRLA/Friday Night Dance and enlisted KRLA disc jockey Bob Eubanks as master of ceremonies. The group’s first of six singles was “Rainbow Stomp – Part 1” (b/w “Rainbow Stomp” – Part 2,” Linda 104) released that March, the same month they played the National Orange Show in San Bernardino. The success of the live album led to gigs at El Monte Legion Stadium, Cinnamon Cinder (Studio City), Pacific Ocean Park (Santa Monica), Pop Leuder’s Park (Compton), and a show for the NAACP in Santa Monica April 11. They also appeared on local television shows P.O.P. Dance Party, The Wink Martindale Show, and the Rock-n-Rudy Harvey Show.

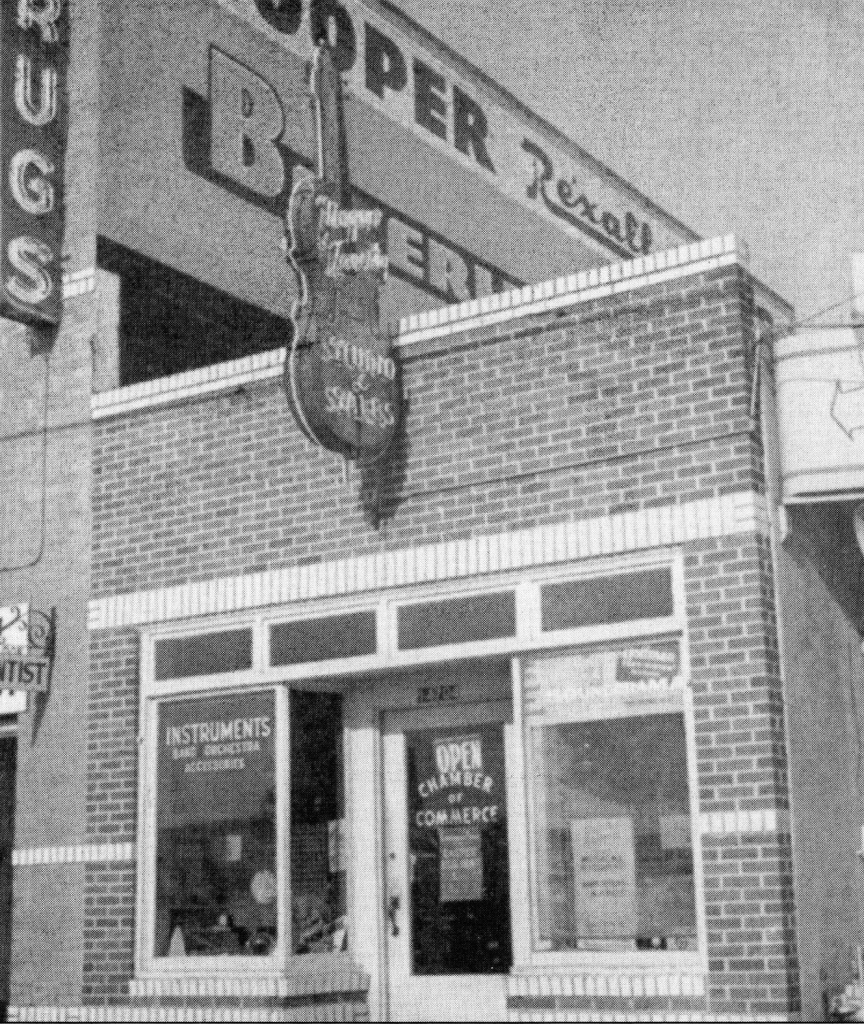

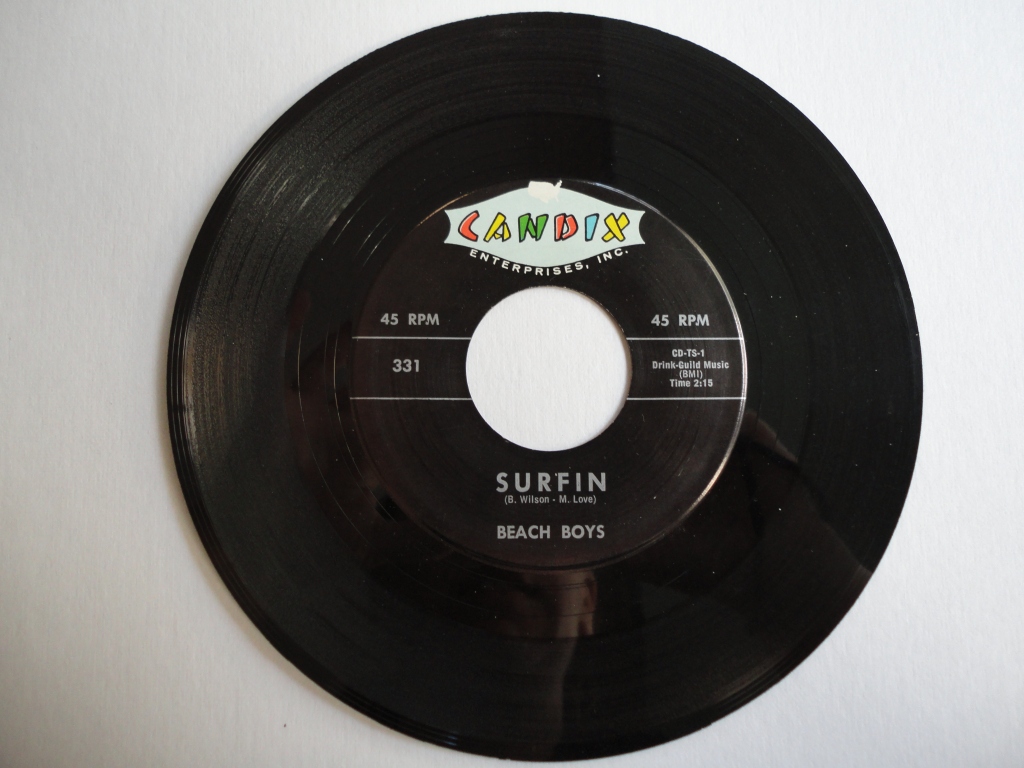

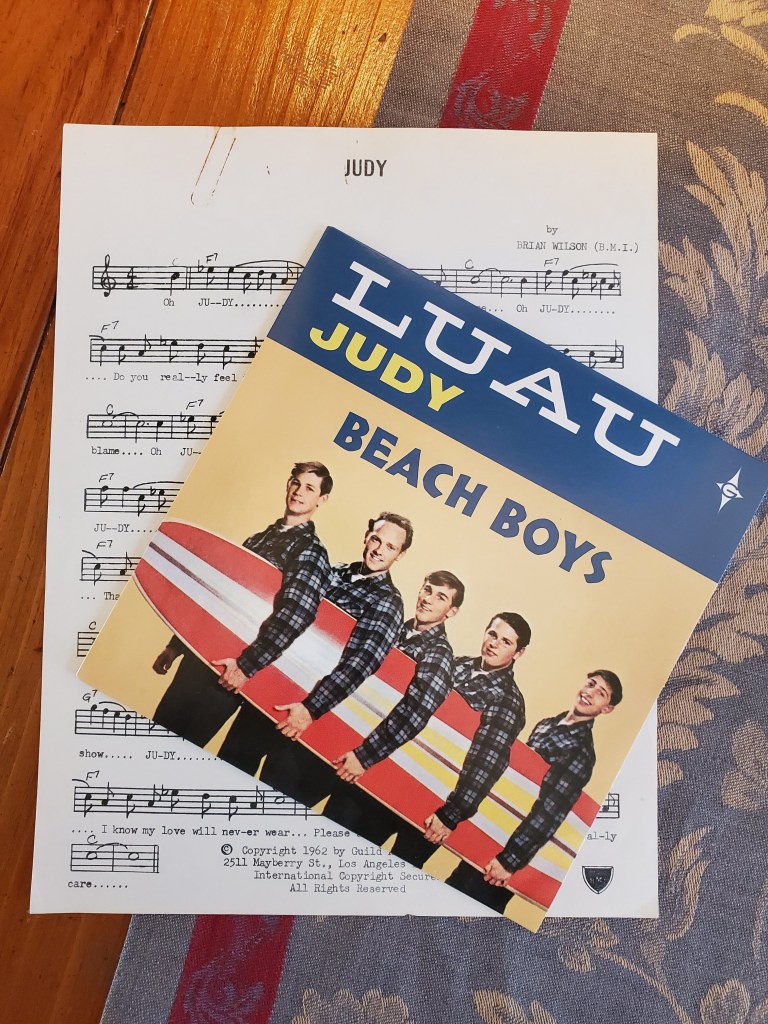

The group’s first of six singles was “Rainbow Stomp – Part 1” (b/w “Rainbow Stomp” – Part 2,” Linda 104) released that March, the same month they played the National Orange Show in San Bernardino. The success of the live album led to gigs at El Monte Legion Stadium, Cinnamon Cinder (Studio City), Pacific Ocean Park (Santa Monica), Pop Leuder’s Park (Compton), and a show for the NAACP in Santa Monica April 11. They also appeared on local television shows P.O.P. Dance Party, The Wink Martindale Show, and the Rock-n-Rudy Harvey Show. “I would pay them a hundred and fifty dollars to come out on Friday night and play Rainbow Gardens. I had a good relationship with the guys. It was obvious the father was the true boss of what was going on. I always thought Murry was a bit of a bullshitter, but he was in there plugging for his boys. For that, I admired him. I tried to get them to change their name because I felt their name was so regional they wouldn’t have much success out of a coastal area.”

“I would pay them a hundred and fifty dollars to come out on Friday night and play Rainbow Gardens. I had a good relationship with the guys. It was obvious the father was the true boss of what was going on. I always thought Murry was a bit of a bullshitter, but he was in there plugging for his boys. For that, I admired him. I tried to get them to change their name because I felt their name was so regional they wouldn’t have much success out of a coastal area.”

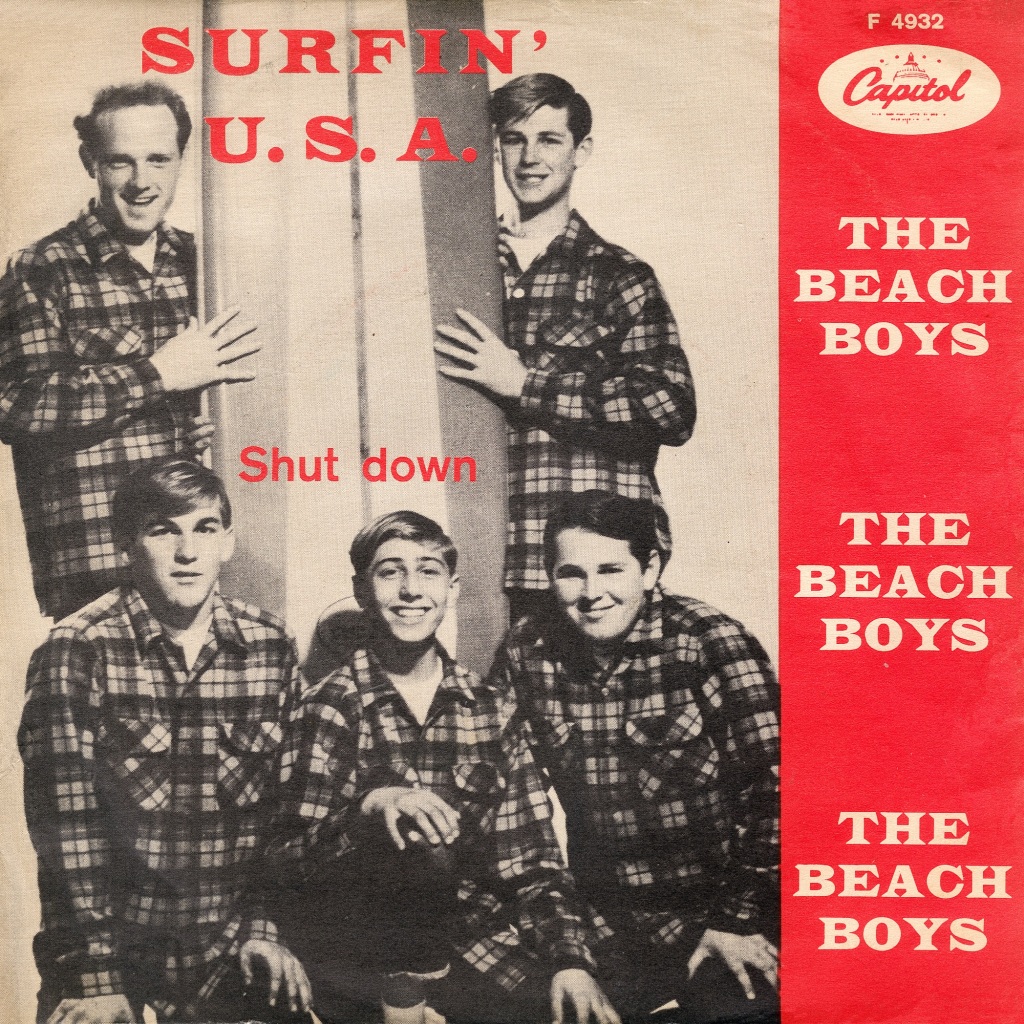

“Shut Down” began life as a thirty-two line composition called “Last Drag” Christian wrote in high school about a race between a Chevy Impala and an Oldsmobile 88 that ends at a treacherous patch of road called Dead Man’s Curve. The song referred to the cars as “shorts,” slang for a hot ride or cool set of wheels, and the relatively short wheel base of the cars. For those in the know, the race was illegal because it happened on the strip where the road was wide.

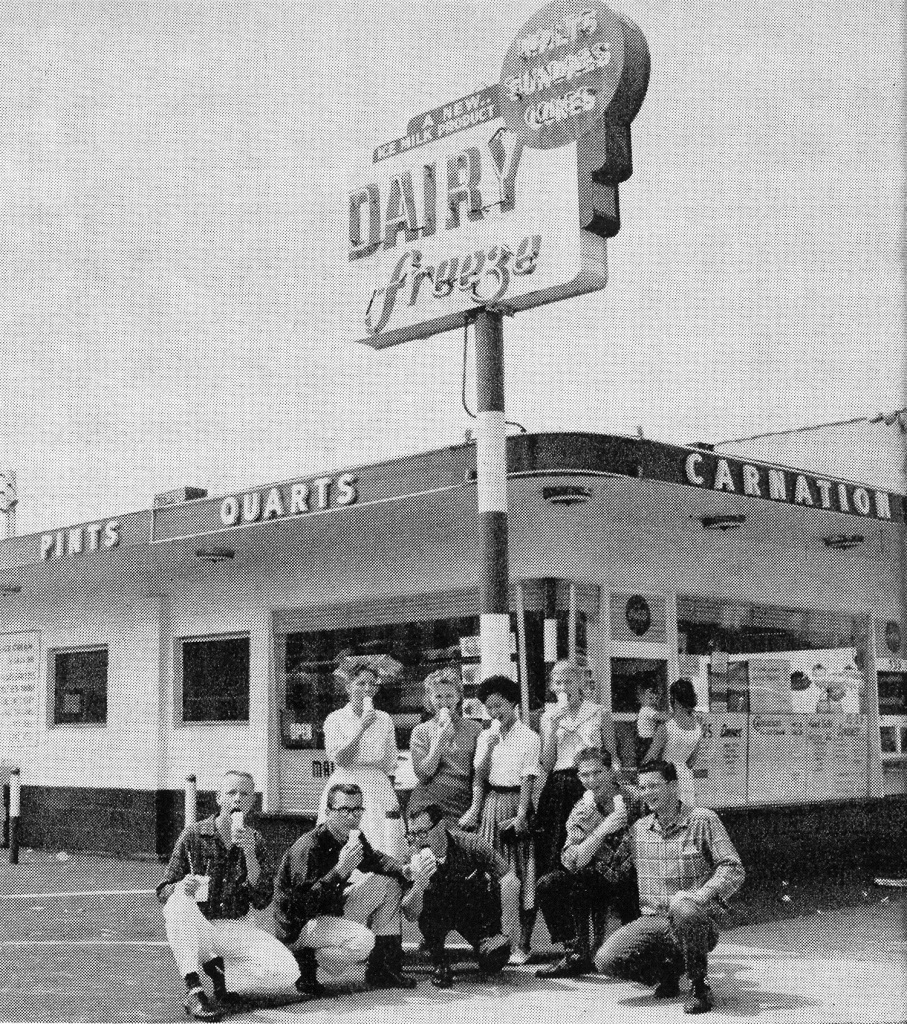

“Shut Down” began life as a thirty-two line composition called “Last Drag” Christian wrote in high school about a race between a Chevy Impala and an Oldsmobile 88 that ends at a treacherous patch of road called Dead Man’s Curve. The song referred to the cars as “shorts,” slang for a hot ride or cool set of wheels, and the relatively short wheel base of the cars. For those in the know, the race was illegal because it happened on the strip where the road was wide. So, where did Brian and Roger devour their ice cream sundae concoctions?

So, where did Brian and Roger devour their ice cream sundae concoctions?