B

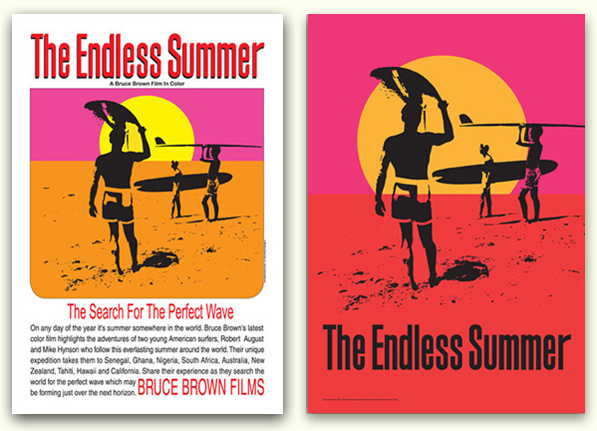

ud Browne was the originator of the surf film genre and the first to make surf films for a commercial market. His first surf film, Hawaiian Surfing Movie, debuted in 1953 at Adams Junior High School in Santa Monica. Tickets were sixty-five cents. “After introducing the film on stage,” recalled Browne, “I hurried up to the projection room to join the operator of an arc projector I had hired. I could see the screen from a small window. I had a microphone in hand and a tape player with music. It was a nervous time, trying to coordinate telling the projectionist when to switch from sound to silent speed and vice versa, playing music in some places and not in others, and narrating when needed. Sometime during the show, I remember the take-up reel quit turning and much of the forty-five minute reel of film piled up on the floor. Although this was sort of a nerve wracking experience, I’ve always thought of the overall event as going very well.”

Browne filmed in Hawaii during the winter, edited and spliced the footage together the following spring, and showed it up and down the California coast that summer. He got the surf film idea from Warren Miller’s ski films and, in a sense, carried forward the work of John “Doc” Ball, the dentist and surfer who photographed and shot 16-mm footage of the California surfing scene in the 1940s. For roughly four years (1953-1956), Browne was pretty much the only guy making surf films.

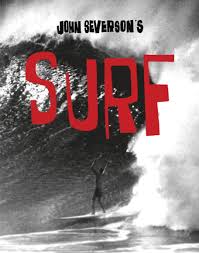

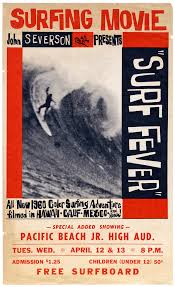

In 1957, Browne released The Big Surf and Greg Noll entered the market with his first surf film, Search for Surf. Over the next four years, Noll had four or five films with that title and they became promotional vehicles for his own line of surf boards. In 1958, Browne explored the surf scene in Australia and New Zealand with Surf Down Under, and a felt a little more competition when he returned to California as two new film makers had entered the field. John Severson’s first surf film was simply titled Surf. Bruce Brown (no relation to Bud and spelled without the “e”) made an impressive debut with Slippery When Wet.  In 1959, all four major surf film makers released new films – Cat on a Hot Foam Board (Bud Browne), Surf Crazy (Bruce Brown), Surf Safari (John Severson), and Surfin Highlights (a compilation by Greg Noll) – and yet another film maker, Walt Phillips, debuted with Sunset Surf Craze. So, during summer 1959, as Brian and Al prepared for their senior year at Hawthorne High School, there were plenty of surf films to check out. In April 1960, Browne offered Surf Happy. Meanwhile, Severson published his debut issue of Surfer magazine to promote his third film, Surf Fever.

In 1959, all four major surf film makers released new films – Cat on a Hot Foam Board (Bud Browne), Surf Crazy (Bruce Brown), Surf Safari (John Severson), and Surfin Highlights (a compilation by Greg Noll) – and yet another film maker, Walt Phillips, debuted with Sunset Surf Craze. So, during summer 1959, as Brian and Al prepared for their senior year at Hawthorne High School, there were plenty of surf films to check out. In April 1960, Browne offered Surf Happy. Meanwhile, Severson published his debut issue of Surfer magazine to promote his third film, Surf Fever.

Severson was born in 1933 and raised in the Pasadena and San Clemente area. He began surfing when he was thirteen years old. In high school, his creativity expressed itself through newsletter editing, photography, cartooning, painting, and surfing. In 1949, he thought about publishing a surf-related magazine, but shelved the idea thinking there wasn’t enough interest to make it commercially viable. He was an art major in college and, in 1955, painted an abstract scene of the San Clemente pier with “Be bop surfers and pointy little surf boards.” After college, he entered the U.S. Army and was stationed in O’ahu, Hawaii, where he continued to surf. Influenced by the surf films of Bud Browne, he made a 16-mm color movie called Surf. He spliced taped music together and wrote a script that could be narrated live while the film was being shown. He drew and block-printed a dramatic black and white handbill to promote the film. The word SURF towers over a hollow outline of a tiny surfer emerging from a monstrous jagged wave. Severson was unable to leave Hawaii, so he asked his friend and fellow surfer Fred Van Dyke to show it in high school auditoriums and other halls along the California coast. After his discharge from the Army in 1958, Sever son made a second film called Surf Safari and in 1959 took it on the road himself. “The first real film was Surf Safari,” he recalled. “Where I had a chance to devote myself to the whole production. I liked Henry Mancini and I liked that Peter Gunn theme. And I had taken a picture of my board, holding a Voit rubber bag with a movie camera in it, and shot my feet surfing to a red board, blue/green water, white foam flying, and little bubbles on the board bouncing off the wax, it was just great. Screaming audiences, standing ovations. In the middle of the film, they would just stand up and cheer, it was a wondrous time.” He found surfers were hungry for images of surfers and monster waves. The small 9″ x 12″ handbills promoting his movies would disappear from the telephone poles on which they were stapled. And Bud Browne was selling black and white stills from his films for a buck apiece. To promote his 1960 film, Surf Fever, Severson produced a black and white Annual he called Surfer that morphed into the first magazine devoted to the sport.

son made a second film called Surf Safari and in 1959 took it on the road himself. “The first real film was Surf Safari,” he recalled. “Where I had a chance to devote myself to the whole production. I liked Henry Mancini and I liked that Peter Gunn theme. And I had taken a picture of my board, holding a Voit rubber bag with a movie camera in it, and shot my feet surfing to a red board, blue/green water, white foam flying, and little bubbles on the board bouncing off the wax, it was just great. Screaming audiences, standing ovations. In the middle of the film, they would just stand up and cheer, it was a wondrous time.” He found surfers were hungry for images of surfers and monster waves. The small 9″ x 12″ handbills promoting his movies would disappear from the telephone poles on which they were stapled. And Bud Browne was selling black and white stills from his films for a buck apiece. To promote his 1960 film, Surf Fever, Severson produced a black and white Annual he called Surfer that morphed into the first magazine devoted to the sport.

World champion surfer Mike Doyle recalled the viewing of Bud Browne’s Surf Happy at the Pier Avenue School in Hermosa Beach. “I was driving home from work one day, when I pulled up to a corner stoplight and noticed a poster stapled to a telephone pole. The poster was advertising a new surf movie that was going to play at the Pier Avenue School. There was a photo on the poster of a powerful, Hawaiian-looking wave. The surfer in the photo was leaning hard into the wave, crouched down with one hand on the rail and one hand raised in the air. There was something vaguely familiar about it. Then I realized the film was Bud Browne’s latest, Surf Happy, and the surfer on the poster was me. Some people have forgotten how surf movies were distributed in those days. The regular film distribution channels were not open to surf movies. There just weren’t enough surfers to make it worthwhile for the big film distributors. So filmmakers like Bud Browne, John Severson, and Bruce Brown, had to create their own channels. Every little beach town up and down the coast had a civic auditorium, a high school, a YMCA, that could be rented for one or two nights. The filmmaker would send out a crew a few days in advance of the showing to nail posters on telephone poles and bulletin boards. Then the news would spread by word of mouth. The filmmaker would roll into town with the film the day of the showing and help set up chairs in the auditorium. He would even sell the tickets at the door. Because a lot of the early films didn’t have sound, he would do his own live narration. If a good crowd turned out, he might have enough money to get a motel room for the night. If not, he would sleep in his car.”

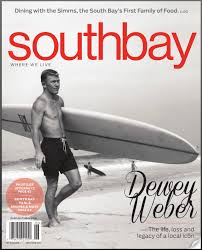

David Earl “Dewey” Weber was one of the legendary surfers in southern California in the 1950s and 1960s. Weber was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1938, an only child of a middle-class German couple. His father, Earl, drove a truck, and his mother, Gladys, worked at the Nabisco cracker factory. His babysitter was also a lifeguard at the municipal pool, so by age four, Dewey could swim the length of the pool twice underwater. Born with two webbed toes on each foot, his aptitude for the ocean seemed pre-destined.

The family moved to California in 1943 when Dewey was five and settled into Manhattan Beach. He learned to fish off the pier with his mother and her friends and, as he got a little older, spent hours watching the ocean exploits of surfers. When he was nine, a local surfer named Barney Biggs spotted him watching from the pier and offered him a used eleven-foot board that probably weighed twice what he did. It took him two years before he could actually ride a wave. But he persisted and, for the next several years, honed his skills. In 1951, Earl Weber acknowledged his son’s perseverance and loaned him thirty-five dollars to buy a used board from Bev Morgan, a local surfer.

The early surfboards were redwood behemoths, eleven feet long and more than 100 pounds. Many of the scientific and technological advancements made through wartime research and development found peacetime domestic applications. Surfing was the beneficiary of at least two such advancements. Water-proof glue, developed prior to World War I, enabled a surfboard’s component wood pieces to be glued together rather than bolted. Advances in the chemistry of resin, fiberglass, and styrofoam during World War II enabled surfboard makers like Bob Simmons to develop the so-called Sandwich Board, sealed plywood over a styrofoam core coated with fiberglass and resin. By the early 1950s, guys like Simmons, Joe Quigg, Matt Kivlin, and Dale Velzy, revolutionized surfboard manufacturing by working with these lighter materials.

As the sport grew in popularity, surfers formed clubs generally based on where they surfed, like the 1st Street Gang, the 17th Street Gang, the 22nd Street Gang, and the Palos Verde Surfing Club. “The South Bay surfers were really ripping at that time,” recalled Mike Doyle. “Guys like Dewey Weber, Henry Ford, Freddie Pfahler, Mike Zuetell, and Peff Eick, had their own clique, the 22nd Street Gang. They all lived in Manhattan or Hermosa Beach and they all went to Mira Costa High. They hung out at the wall on 22nd Street, just north of the Hermosa pier, which was the coolest place in Hermosa Beach. And where there were two or three great hamburger joints and the famous Green Store on the corner. They had their own style of talking and dressing.

“They had their own little world and I wanted so badly to be part of it.”

They wore faded jeans, blue T-shirts, bitchin’ blue tennis shoes, and wore St. Christopher medals around their necks. Dewey Weber, who was a yo-yo champion, sometimes broke the gang’s dress code by wearing his red Duncan Yo-Yo jacket but, other than that, they always looked like perfect clones of each other. And they did everything together. They surfed together in the morning and they drank together every night. All weekend long, they’d be standing there in front of the wall, talking about who got laid the night before, who got drunk, and who got put in jail. They’d be all hung over with vomit stains on their pant cuffs and seaweed wrapped around their necks. They had their own little world and I wanted so badly to be part of it.”

One of the most prestigious clubs was the Manhattan Beach Surf Club. Members obtained permission from local authorities to build a 15′ x 40′ clubhouse among the pilings under the Manhattan Beach pier. City officials hoped the clubhouse would help contain the unkempt surfers to just one part of the community. Club members wore a distinctive leather thong tied in a square knot around their left ankles and woe to the non-member gremmie who dared wear one. One brave soul who wore a thong despite being denied membership was stripped naked and tied to a stop sign. One of the club’s most colorful and influential members was Dale Velzy who, with the help of his cabinet-maker grandfather, shaped his first board when he was ten years old. As a kid he earned the nickname Hawk because he could spot a coin in the sand from a great distance. After a two year stint in the Merchant Marines during the war, Velzy was back shaping redwood/balsa combination boards for his friends in the clubhouse. When the wood shavings got to be too much for the clubhouse, he opened Velzy Surfboards in Manhattan Beach in 1950.

In 1953, Henry “Hap” Jacobs and Bev Morgan opened Dive N’ Surf. Jacobs made boards and Morgan made wetsuits. A year later, Hap and Hawk joined forces and opened Surf Boards by Velzy and Jacobs at 4821 Pacific Avenue and Manhattan Beach Boulevard near the Hermosa Beach pier. They made about a dozen custom balsa boards a week. Velzy would shape them from the blanks (lengthy boards glued together on which the shape of the board was drawn and then cut) and Jacobs would glass them (apply the polyurethane). They became the largest manufacturer of surfboards on the coast.

Dewey Weber played quarterback his freshman year at Mira Costa High School in 1952. But at 5’3″, muscular and wiry, he was better suited for wrestling at which he lettered as a freshman and was California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) wrestling champ for three years. “We had a group at school that was mostly surfers and we ran the place,” recalled Weber. “The other group was the lowriders. Both groups were very close. They rode their motorcycles and hopped up their cars, and we surfed. We came together against all the football players. It worked out great.”

Dale Velzy began providing Weber, then a high school sophomore, with free boards in exchange for promoting his boards and shop. The arrangement was informal, but it was basically an early form of corporate sponsorship. In 1955, Velzy introduced his Pig board which made turning much easier. “This board was narrow in the nose and wide and curvaceous in the tail,” said Paul Holmes, author of the biography Dale Velzy is Hawk. “It is counter-intuitive, but it happened to turn really well.” The Pig board helped Weber pioneer a style described, in the good sense of the word, as hotdogging because of his skillful showmanship. Weber earned the nickname “Little Man on Wheels” because of his ability to walk the board really fast and maneuver in and out of the wave.

Weber graduated high school in 1956, worked as a lifeguard at the Hermosa Biltmore Hotel, and then headed to Hawaii with about a dozen surfer buddies to ride the legendary waves at Makaha. Some of his exploits were captured in The Big Surf, Bud Browne’s 1957 film documenting big wave riding on the famed north shore.

In 1957, Velzy and Jacobs financed twenty-year-old surfer and aspiring film maker Bruce Brown. Velzy accompanied Brown into a camera shop, peeled off a stack of hundred dollar bills, and bought him a couple of thousand dollars worth of equipment to film his first movie Slippery When Wet released in 1958. Filmed in California and Hawaii, Slippery featured footage of Dewey Weber and a soundtrack by jazz saxman Bud Shank. On November 5, 1957, Greg Noll sliced himself a piece of surfing history when he surfed Waimea Bay after a fatality there years earlier had made it virtually off limits.

Business at Velzy and Jacobs was good and, in 1959, they opened a second shop in San Clemente. But later that year, Velzy bought out Jacobs and the two parted amicably. Velzy retained the two shops and Jacobs later opened his own shop at 422 Pacific Coast Highway in Hermosa Beach. When Weber returned to California in 1960, he worked as a lifeguard and managed Velzy’s Venice shop for $200 a week, which was good money at the time. By the late 1950s, the use of polyurethane foam and fiberglass revolutionized surfboard manufacturing. Lighter boards attracted lots of new people to the sport. Average folks could now actually carry a board from their car to the ocean. Business skyrocketed. Velzy introduced an 11/10 credit plan whereby eleven dollars put you on a board and ten monthly payments of ten dollars each made the board yours. Velzy had two factories supplying five shops and was selling 150-200 boards a week. Outwardly he showed all the signs of success. He drove a gullwing Mercedes 300SL, smoked big cigars, wore a large diamond pinky ring, ran with the Hollywood crowd, and always had a beautiful woman on his arm. Business was booming, but nobody was sending Uncle Sam his share of the sales. One morning Velzy found his San Clemente shop padlocked for income tax irregularities. The Internal Revenue Service came down hard on him and sold his inventory to defray what he owed in taxes.

While Velzy was still trying to figure out a way to get back his business, Weber leased the Venice shop for $1,500 a month and started his own business. That didn’t sit too well with Velzy. Details surrounding what happened to Velzy’s blanks (raw inventory ready to be shaped into boards) and his tools remain shrouded in controversy. “Surfing has a dark side,” said Joe Doggett in an interview in the Houston Chronicle after Weber died. “It’s a maverick lifestyle; it attracts the renegades and cavaliers and one-eyed jacks. It has no place for the dull and ordinary. Surf stars, like rock stars, cannot control the power and the beauty that they possess.”

For most of the 1960s, Weber was the world’s largest manufacturer of surfboards, turning out 300 boards a week. Velzy and Weber never spoke to each other again. Weber died in 1993 from the cumulative effects of alcoholism and Velzy died from lung cancer in 2005. Both men had a profound impact on the sport they loved.

Hermosa Beach has a rich history associated with surfing. Hermosa is Spanish for beautiful and Hermosa Beach lies between Manhattan Beach to the north and Redondo Beach to the south. In the early part of the twentieth century an acre of ocean-front property there sold for thirty-five dollars. One of the most distinctive structures in Hermosa Beach is the Municipal Pier which juts out into the Pacific Ocean from Pier Avenue. The first pier, built in 1903, was 500 feet long and made of wood. A little inland along Pier Avenue sits the aptly named Pier Avenue School on the southwest corner of Pier Avenue and Pacific Coast Highway. After an earthquake destroyed the original school in 1933, construction on a new school began in 1934 and continued as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The school was sold in 1978 to the City of Hermosa for the Hermosa Beach Community Center which is also home to the Hermosa Beach Historical Society Museum. In Hollywood’s golden era, Hermosa Beach was a favorite hideaway for film stars. Charlie Chaplin had a summer home there and newlyweds Clark Gable and Carole Lombard honeymooned at 4 The Strand, the wooden walkway that runs parallel with the Pacific Ocean.

In 1907, twenty-four-year-old George Freeth, Jr., gave a surfing exhibition in a cove near Hermosa Beach. Over the next dozen years, in addition to spectacular displays of athleticism in the water, Freeth trained volunteer lifeguards, developed rescue techniques and equipment still used today, and eased people’s fear about venturing into the ocean.

In 1907, twenty-four-year-old George Freeth, Jr., gave a surfing exhibition in a cove near Hermosa Beach. Over the next dozen years, in addition to spectacular displays of athleticism in the water, Freeth trained volunteer lifeguards, developed rescue techniques and equipment still used today, and eased people’s fear about venturing into the ocean.

In 2001, writer Arthur C. Verge published “George Freeth: King of the Surfers and California’s Forgotten Hero” in the California Historical Society’s magazine California History. It is a fascinating read and can be found at legendarysurfers.com. In 2009, an Irish film company produced Waveriders, a documentary about surfing off Ireland’s rugged coast and the sports’ Irish roots through Freeth. Today, Freeth is considered the Father of California Surfing.

George Douglas Freeth, Jr., was born November 9, 1883, on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. His father, George Freeth, Sr., a seaman from Ulster, Ireland, was part of the tide of Irish immigrants that washed up on the American shore in the late 1870s. He was quite the adventurer because, rather than settle on the east coast as many Irish did, he pushed westward and eventually settled in Hawaii. There he met and married Elizabeth Green whose father, William Lowthian Green, had been born in London and helped establish an inter-island shipping company among the Hawaiian islands and, later, the Honolulu Iron Works. Green’s business acumen led to his appointment as Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs. Freeth and Elizabeth had six children including George, Jr. As a boy, young George displayed tremendous skill as a swimmer and diver, both in salt water pools and the warm rolling surf off nearby Waikiki, where he was selected captain of the Healani swim team. When he was eight or nine years old, a Hawaiian prince presented him with a surfboard as a symbolic gift of Hawaii’s cultural link with the water sport. By the time Freeth turned seventeen at the turn of the century, surfing had all but disappeared from the Hawaiian Islands. For eighty years, New England missionaries seeking converts to Calvinism, had frowned upon surfing as an unproductive, licentious pastime that led to gambling and promiscuity. But Freeth was captivated by the adventure and sheer exhilaration of the sport. He started surfing daily and had a natural athletic ability in the water. One of his early admirers was Duke Kahanamoku, seven years his junior, the legendary swimmer and surfer who would go on to break the world record in the 100 meter freestyle capturing the gold medal in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. Freeth was ineligible to compete on the U.S. team because his paid experience as a lifeguard rendered him a professional.

In 1907, Freeth befriended two authors who would have a profound effect on his life. Alexander Hume Ford, a middle-aged travel and adventure writer originally from South Carolina, settled in Oahu, began researching Hawaiian culture, and became fascinated with surfing.

One day, as Ford struggled in the surf to stay atop his board, Freeth swam over and provided some helpful lessons. The two kindred spirits became fast friends. Ford wrote of Freeth’s exploits and together they helped promote surfing through the Outrigger Canoe and Surfboard Club at Waikiki, which Ford helped establish. In May 1907, Ford and Freeth accompanied a United States congressional delegation on a fact finding mission to determine Hawaii’s eligibility for statehood.

On April 23, 1907, the author Jack London, along with his wife and a small crew, sailed out of San Francisco on his yacht Snark destined for the Hawaiian Islands.  London had written seven novels in the last five years and was world renowned for The

London had written seven novels in the last five years and was world renowned for The  Call of the Wild, White Fang, and The Sea-Wolf.

Call of the Wild, White Fang, and The Sea-Wolf.

As Freeth escorted the congressional delegation to the smaller islands, Ford remained at Waikiki where, on May 23, he met London at a restaurant in the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. The two men, each aware of the other’s literary contributions, hit it off immediately. London was spellbound by Ford’s colorful descriptions of surfing and wanted to try the sport himself. Upon Freeth’s return, Ford introduced him to London and the three men surfed together. London was impressed with Freeth’s physical prowess in the sea. He wrote an article entitled “Riding the South Sea Surf” that appeared in the Women’s Home Companion, in October, 2007 in which he described Freeth, “He is a Mercury—a brown Mercury. His heels are winged, and in them is the swiftness of the sea.” He also described Freeth as “half-Hawaiian, half-Irish, and all Greek god.”

Freeth’s association with Ford and London was relatively short-lived. Like his father, he, too, had the wanderlust gene. He longed to see more of the world and soon asked both writers for letters of introduction. On July 3, 1907, with his letters safely tucked away, he boarded the passenger ship Alamdea bound for San Francisco. Within weeks, he trekked further south and began surfing off the coast of Venice, California, and drawing crowds of curious onlookers. An article in the July 22 Daily Outlook, a local newspaper based in Santa Monica, carried a story of his exploits under the headline “Surf Riders Have Drawn Attention.”

Freeth’s arrival in southern California and his mastery of the waves was a particularly fortuitous occurrence for two real estate developers looking for new ways to attract tourists to the coastal resort towns they had constructed over the last few years. In the early part of the 20th century, Americans generally did not venture into the ocean. The idea of wading into the vast, seemingly infinite ocean was just too terrifying. Instead, they swam in the safety of salt water pools built adjacent to the shoreline. In 1905, tobacco millionaire Abbott Kinney opened Ocean Park on the northern end of a two mile piece of property he owned just south of Santa Monica. On the southern end he built a resort called Venice in America, complete with canals, a 1,200-foot long pier with an auditorium, a ship restaurant, a dance hall, a hot salt-water plunge tank, and a block long business street whose stores boasted Italian architecture inspired by their namesake city.

Tourists rode a small tram around Venice and were whisked along its man-made canals in gondolas.  People arrived in Venice by the red cars of the Pacific Electric Railway owned by Henry E. Huntington, a wealthy Los Angeles real estate developer who owned most of Redondo Beach and had built a resort there whose centerpiece was a three-story Moorish pavilion with a second-story ballroom that held 1,000 revelers.

People arrived in Venice by the red cars of the Pacific Electric Railway owned by Henry E. Huntington, a wealthy Los Angeles real estate developer who owned most of Redondo Beach and had built a resort there whose centerpiece was a three-story Moorish pavilion with a second-story ballroom that held 1,000 revelers.

Both Kinney and Huntington found that real estate sales were impeded by the public’s perception that beach homes and their proximity to the ocean was too great a temptation, and danger, for young children and teenagers. Huntington and his wife, Margaret, led a community effort to form a local group of volunteers and purchase a small boat for ocean rescues. Huntington reasoned that if the public felt safe in the ocean, they would be more apt to consider buying one of his homes. But in June, just about a month before Freeth arrived in southern California, the rescue boat capsized and a volunteer member of the Venice Lifesaving Crew drowned as his fellow members watched from the shore helpless to save him. The news story frightened people and reinforced their reluctance to venture into the ocean. Kinney and Huntington saw disaster looming on the horizon.

It wasn’t long before Kinney and Huntington became aware of George Freeth (perhaps through the July 22 newspaper article) and realized he could help them promote the fun of going in the ocean, offer swimming and water safety lessons, and train a more professional lifesaving team. Freeth was soon commuting between Venice and Redondo Beach on the red cars of the Pacific Electric Railway. Huntington hired him to perform twice daily surfing demonstrations on Moonstone Beach, so named for the mound of semi-precious stones on the shore from which men were encouraged to choose “an excellent specimen” for their sweetheart. He promoted Freeth as the “Man Who Can Walk on Water.”

On August 24, 2007, the Venice Volunteer Life Saving Crew, through the fund raising efforts of Kinney’s wife, Margaret and the Pick and Shovel Club, purchased a metal lifeboat they christened Venice. The Pacific Electric Railway soon donated a second boat. They also had a small mortar cannon to sound the alarm when a boat or swimmer was in distress. With the equipment in place, Freeth set about training the men. One of his pioneering efforts was the then unheard of technique of swimming out to the swimmer in distress rather than waiting for a crew to assemble and row out in the rescue craft. Within months of his arrival in California, Freeth was elected captain of the Venice Life Saving Crew and presented with a gold watch on his twenty-fourth birthday.

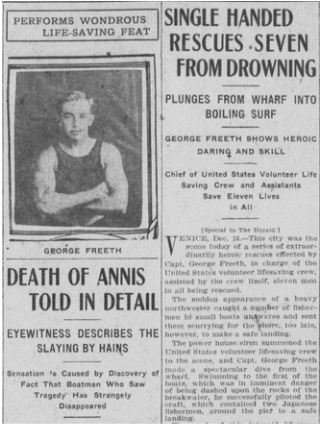

Over the next dozen years, Freeth introduced many life-saving techniques and devices such as the torpedo-shaped rescue buoy which lifeguards still use today. He also established the first lifeguard station and introduced water polo to the west coast. He was awarded the Gold Medal of the U.S. Lifesaving Corps., for rescuing seven Japanese fishermen when they got caught in a sudden winter squall in Santa Monica Bay on December 16, 1908. Freeth dove off the Venice pier and battled gale force winds and frigid temperatures for more than two and one-half hours. Despite severe hypothermia and exhaustion, he dove repeatedly to rescue the men. At one point, he single-handedly kept three fishermen afloat in the churning sea.

The next day, he and his crew were back at their stations. Just another day at work. Waiting for him were the fishermen whose lives he saved. They presented him with yet another gold watch and a financial donation to the life-saving cause. They renamed their small fishing village, at the foot of the Long Wharf in what is now Pacific Palisades, Port Freeth.

- December 17, 1908 Los Angeles Herald on rescue of Japanese fishermen

- Gold Medal awarded to Freeh by the U.S. Life saving Corps.

Source:

Malcolm Gault-Williams. “Legendary Surfers, A Definitive History of Surfing’s Culture and Heroes,” legendarysurfers.com.

Another’s great article. A few years back, just before his sad passing, I tracked down and interviewed surfer Les Williams – the infamous rider on the front of the Surfin’ USA album cover – and he recalled fondly those halcyon days of the late 50s and early 60s. The interview later ran on my now-defunct Beach Boys Album Covers website but can also be found in a copy of ESQ from a few years back.

Les kindly signed the album sleeve for me as well. Lovely guy…

LikeLike

Ha ! Just reading the book only to find my name credited in it for the interview I held with Les !! Cool…

Thanks so much 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, yes, I’m a staunch believer in giving credit where credit is due. As you know, every book builds upon the books preceding it. Thank you Malcolm for your support of Becoming the Beach Boys and for your own excellent work documenting the history of America’s greatest band!

Jim

LikeLike

The dynamic surrounding George Freeth’s arrival in So Cal has long been a subject of interest to me: “who did what when” that precipitated Freeth’s arrival in Santa Monica. There are lots of versions, with precious little evidence to support. If Freeth arrived with letters of introduction, we know this how? Has anybody actually seen these letters? Did anybody make a copy? Do they exist in some archive? That Freeth arrived in the South Bay by his own volition is a fresh alternative to long held version of Henry Huntington hiring him from Hawaii. By the way Henry Huntington’s fist wife was named Mary Alice, not Margaret.

LikeLike

I am really sorry to have to burst the bubble, but I’ve done extensive research into the family background of the surfing legend George Douglas Freeth and I am sad to report that there is not any truth to the contention, as promoted in the ‘Waveriders’ film of 2009, that he had any Irish blood in him at all. His father, George Douglas Freeth Snr, who was born in Hythe, in Kent, England, in March 1855, and who died in London in 1914, was not a ‘seaman from Ulster’. In fact, Freeth’s ancestors, who are closely associated with Birmingham in England, as far back as the 1730s, were all senior (and some were knighted) officers in the British army.

LikeLike